Typically, when an aircraft engineer is asked to construct a 16-layer carbon fiber fuselage for something as large as a 787 Dreamliner, they have to use an oven about as big as a mansion just to get the job done. The industrial-sized monster of a machine engulfs the multiple layers of polymer with up to 750 Fahrenheit degrees of heat – wasting considerable amounts of time, space, money and energy – and combines them into a single, solid composite material.

I say typically, because now, thanks to a handful of Aerospace engineers over at MIT, a fingernail-thin slice of film, made up of carbon nanotubes (CNT), may soon be able to replace the conventional cul-de-sac-sized ovens using a fraction of a fraction of a fraction of the energy – or 1 percent of it, if you’re looking for numbers.

“To cook a fuselage for an Airbus A350 or Boeing 787, you’ve got about a four-story oven that’s tens of millions of dollars in infrastructure that you don’t need,†says Brian L. Wardle, an associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT.

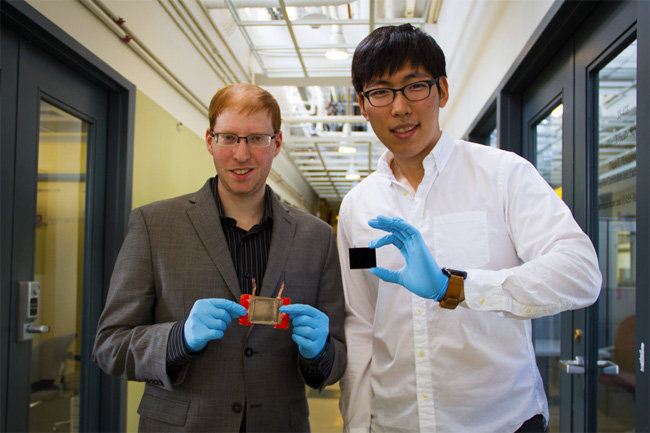

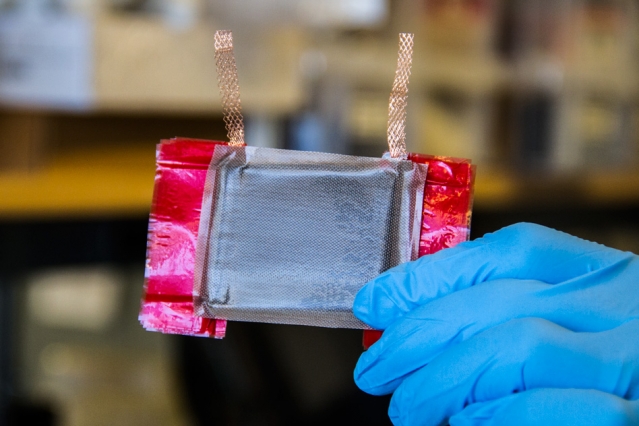

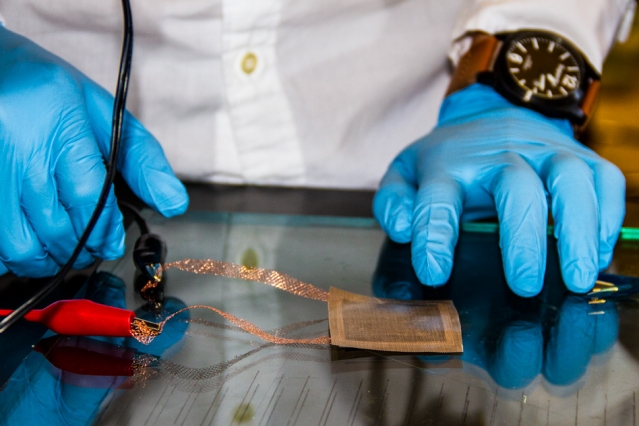

What Wardle and his team – which includes MIT graduates Jeonyoon Lee and Itai Stein, as well as Seth Kessler of the Metis Design Corporation – have cooked up instead is a more direct method. Instead of baking the pre-composites, which, thanks to preheating and wasted space, means loads of unused energy, they wrap the polymer layers up like presents on Christmas Eve, connect the extended ends up to an electrical power source and let the almighty electricity to do its thing.

“Our technique puts the heat where it is needed,†Wardle explains, “in direct contact with the part being assembled. Think of it as a self-heating pizza. Instead of an oven, you just plug the pizza into the wall and it cooks itself.â€

The best part is, after testing it on an oft-used carbon fiber component used in aircraft construction, the fly-sized film was able to create a composite material just as strong as that of one baked in a not-so-easy bake oven.

What’s even more impressive, is that after further testing, the film was able to generate as much as 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit of heat – which far surpasses some of the beastlier bakers, which often fry out when pushed too far.

“There’s no composite we can’t process,†Wardle explains, making note of the ability to work with such blistering temperatures. “This really opens up all polymeric materials to this technology.â€

Unfortunately though, this technology comes with somewhat of a lofty letdown. With all this talk of size, the film is not yet ready for fuselages or wings – the larger parts of a plane – as the team is still working with industrial partners to, one day, hopefully scale up the size for mass (or massive) production.

“There needs to be some thought given to electroding, and how you’re going to actually make the electrical contact efficiently over very large areas,†Wardle admits. “You’d need much less power than you are currently putting into your oven. I don’t think it’s a challenge, but it has to be done.â€

Currently, the functionality is more fitting for those hoping to work on a much smaller scale.

“Smaller companies that want to fabricate composite parts may be able to do so without investing in large ovens or outsourcing,†says Gregory Odegard, a professor of computational mechanics at Michigan Technological University. (Odegard was not involved with the creation or implementation of the film.) “This could lead to more innovation in the composites sector, and perhaps improvements in the performance and usage of composite materials.â€

For more information on this breakthrough technology, you can visit MIT’s official website here.